Overburdened Communities Bear the Brunt of Environmental Injustice

October 27th, 2022

By Ashley J. Lee

Jackson, Mississippi is certainly not the first, nor will it be the last city to suffer the consequences of dangerous and unsafe water. However, it has reminded those who have forgotten about the lack of access to clean drinking water in an alarming number of Black and Latinx communities in our nation.

Black residents make up 82.5% of Jackson’s estimated population of 149,761 people, with 24.5% of residents living in poverty. Most of the city’s residents were provided a boil water notice beginning in late July of this year. According to ABC News, many of the residents were left without water at all after the city’s main treatment facility suffered damage a month later. Jackson’s water system has a long history of problems with over 750 boil notices issued since 2016, making this water crisis a foreseeable event. Access to running water has been restored but remains undrinkable as there are continuing concerns about its quality.

Jackson is not alone in recent water infrastructure crises across our sweet land of liberty. Tens of thousands of residents in Baltimore, Maryland were similarly placed under a boil water order this past September due to the detection of E.coli. Baltimore’s Black residents account for 62% of its estimated population of 576,498 residents with 20% of people living in poverty. According to the Baltimore Sun, the water contamination was discovered and confirmed over Labor Day weekend, but residents were not notified until the following Monday. Unfortunately, the Baltimore Sun also claims that the city’s sprawling system is “aging and main breaks […] are common.” When the boil water advisory was lifted on Friday, only five days after it was issued, residents were assured that the running water was safe for consumption. However, the cause of the E. coli contamination remains unknown.

Lack of access to safe, clean drinking water is emblematic of how segregating low-income communities and communities of color lends to continued environmental injustice. The highest levels of pollution and environmental harm are concentrated in places where poverty levels are high and public and subsidized housing is common. The same holds true in New Jersey, made clear by its significant presence on the Superfund list. The Superfund is a federal program created in 1980 to clean up the nation’s “most polluted and hazardous places.” New Jersey currently has over 100 toxic sites on the Superfund list and only about a third of these sites have been cleaned up after over forty years since the Superfund’s creation.

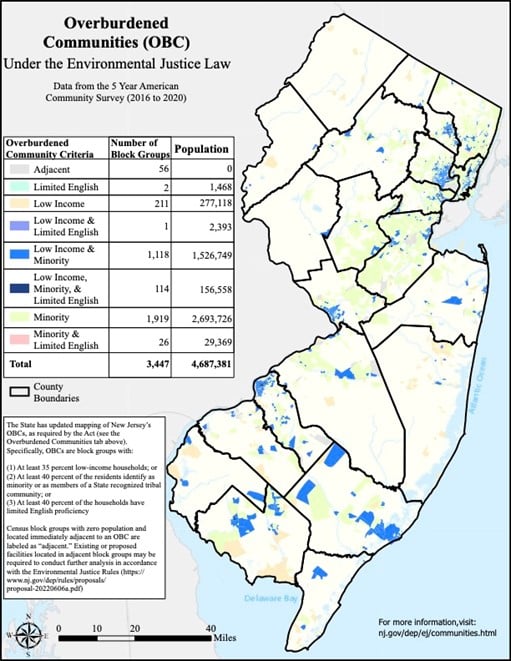

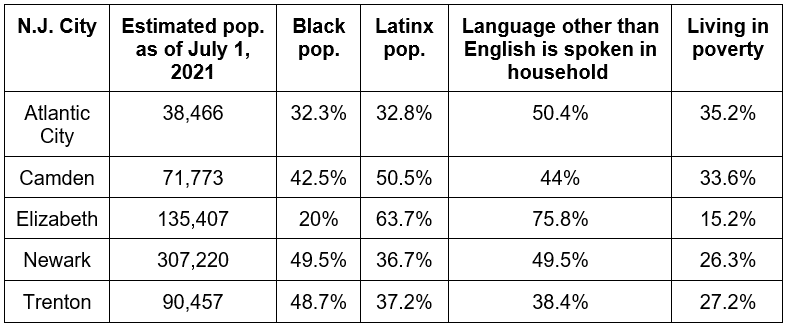

The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Agency (NJDEP) asserts that “low-income communities and communities of color have been subject to a disproportionately high number of environmental and public health stressors, including pollution from numerous industrial, commercial, and governmental facilities located in those communities and, as a result, suffer from increased adverse health effects including, but not limited to, asthma, cancer, elevated blood lead levels, cardiovascular disease, and developmental disorders.” New Jersey has named these communities “overburdened communities.” Many of these communities are majority people of color, have a high number of non-English speaking households, and have a high percentage of households living in poverty.

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool, overburdened communities rank within the 80-100 percentile compared to the national average in the categories of lead paint exposure, hazardous waste proximity, particulate matter 2.5 in the air, and wastewater discharge. The very high lead paint exposure in these New Jersey communities is especially concerning as it is no secret that children’s exposure and consumption of lead is unsafe in any amount and has long-term consequences.

Similarly distressing are the hazardous waste proximity figures, specifically in Newark where nearly half of the population are Black and the majority of the city ranks in the 95-100 percentile for hazardous waste proximity. The Passaic River’s major pollution, consisting of industrial poisons, pesticides, dioxin, and polychlorinated biphenyls (commonly called “forever chemicals”), is a strong contender for the cause. These pollutants and chemicals are the result of toxic spills and dumping and have traveled through associated waterways, spreading the contamination. The river has long been referred to as one of the most polluted waterways in the country while cleanup has been pending for decades.

To help prevent worsening conditions, environmental protection agencies, both federally and on the state level, have created laws to promote environmental justice. The EPA defines environmental justice as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.” In the spirit of environmental justice, New Jersey passed N.J.S.A. 13-1D-157 in 2020, which requires NJDEP to assess whether a facility will impact already existing environmental and health conditions in overburdened communities when reviewing applications to permit certain facilities. This rule applies to eight types of facilities: major sources of air pollution, incinerators, sewage treatment plants, solid waste facilities, recycling facilities, scrap metal facilities, landfills, and medical waste incinerators.

New Jersey has continued to advance environmental justice through a new draft rule, released in early June, that aims to tackle cumulative pollution—an issue that was not addressed by the 2020 law. Currently, permit decisions only consider an individual facility’s environmental impact. Cumulative pollution considers the individual facility’s impact as well as the potential facility’s contribution to pollution from already existing facilities in the community. The draft rule would require denial of permit requests if NJDEP concludes a facility would create or add to an already existing disproportionately high environmental and/or health burden on the community. If enacted, permit requests would be accompanied by reports that evaluate contributions to the cumulative impact. This report would be publicized, and a public hearing would be held before a decision on the permit request is made.

The 2020 law provides a model for other states on how to advance environmental justice in policy. The pending rule would only strengthen and expand its reach and have a positive impact on the path to achieving environmental justice for New Jerseyans.